In the business environment, there are often guidelines as to the manner in which an employee should present himself/herself, in keeping with the corporate image of the employer.

Student Attorney Claire Pascall examined the issue of dress codes and ‘professional’ appearance in the workplace, for the Hugh Wooding Law School’s Human Rights Law Clinic. Claire’s article was published in the Law Made Simple column of the Trinidad Guardian newspaper on Monday November 7th, 2016.

A professional dress code and/or appearance is not specifically defined. However, it generally means the recommended appearance within a particular work environment. The importance and reasoning behind the implementation of a dress code for the workplace varies by industry based on the nature of the industry and this is subject to interpretation of each industry.

For example, professionalism for an employer in a bank may require an employee to wear business attire all year for the position as a teller which requires constant interaction with clients. On the other hand, professionalism for an employee who is a graphic artist in an advertising agency may call for more casual wear such as jeans and a casual shirt.

Legal position in the workplace

Dress codes are guided by policies, practices and norms in various workplaces which establishes the reason an employer may have one. Three main reasons include but are not limited to:

- To be easily identifiable. For example, an airline may require staff to wear uniforms, featuring thelogo of that airline.

- To represent an image to reflect the ethos of the organisation. This can call for the removal of certain body piercings and the covering of tattoos.

- Health and safety purposes. For example, firefighters are required to wear a rigid helmet, hand gloves, a belt, and safety shoes.

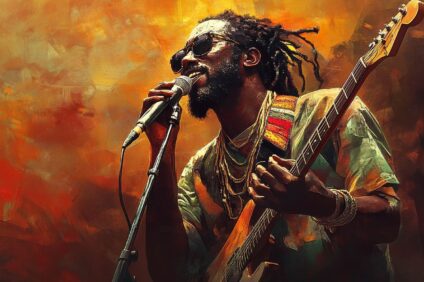

An employer’s policy on dress code should be non-discriminatory, that is, it should apply equally to both men and women. The Equal-Opportunity-Act-Chap.-22:03 mandates that a person should not be discriminated against on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, marital status, origin: including geographical origin or any disability of that person. Thus, a Rastafarian who wears “dreadlocks” based on his religion should technically not face discrimination.

For a policy to be discriminatory it must be ‘less favourable treatment’ rather than ‘different treatment.’ In the UK case of Department-for-Work-and-Pensions-v-Thompson–[2004]–IRLR–348, EAT, The DWP required its job-centre staff to dress in a professional, business-like way. This meant that male staff were required to wear a collar and tie. The same requirement was not made of women, who were merely required to ‘dress appropriately and to a similar standard’. Simply restricting members of one sex to a particular type of clothing whilst members of the other sex were not did not amount to less favourable treatment as common standard had been set for all staff and neither gender had been treated less favourably by the enforcement of that standard, albeit with non-identical results.’

It follows that, policies may have restrictions but these restrictions must be clearly communicated and justified to the establishment of the organisation.

Remedies

- The High Court is not limited to employment matters and offers an alternative method of recourse to any individual.

- Where there is a trade dispute between employer and employee, a report can be made to the Minister of Labour who then determines whether the dispute is unresolved and refer the matter to the Industrial Court: section-59-Industrial-Relations-

- A person who alleges a discriminatory policy can lodge a written complaint with the Equal Opportunity Commission detailing the alleged act: section-30–Equal-Opportunity-Act-Chap 22:03.

Compensatory damages, reinstatement and re-hiring may be awarded if a claim is successful.

Students of the Hugh Wooding Law School Human Rights Law Clinic were each given the opportunity to write an article for the “Law Made Simple” column in the Trinidad Guardian newspaper.

These topics ranged from analysis of specific legislation, to general legal concepts. The aim of this exercise was to teach the students how to write about complex legal issues, for the average newspaper reader.

This article was re-published with permission from the Human Rights Law Clinic.